Source: https://www.rch.org.au/kidsinfo/fact_sheets/Heart_problems_in_children/

About one in every 100 children has a heart problem, which may also be called a heart defect or congenital (present from birth) heart disease. Heart defects can usually be treated with medicine, surgery or other medical procedures.

Most tests for heart problems are simple, quick and not painful. Most children with heart defects live a normal and full life with very few or no restrictions.

Signs and symptoms of heart defects

Many children with heart defects appear healthy and have no symptoms, and their parents do not know they have a heart problem. If children do have symptoms, they often develop in the first few weeks after they are born. Common symptoms include:

- blue colour around the lips and blue skin (cyanosis)

- difficulty feeding (especially becoming sweaty during feeds)

- shortness of breath

- poor growth

- pale skin

- fatigue.

These symptoms result from a reduced oxygen supply to the body, which happens because the blood does not have as much oxygen as usual, or the heart does not pump as well as it should.

How the heart works

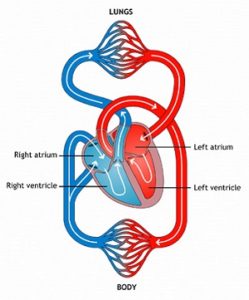

The heart has four chambers (like rooms) – two on each side of the body. The right side collects blood from the body and sends blood to the lungs to collect oxygen from the air we breathe. The left side collects the fresh blood back from the lungs and pumps it to the rest of the body.

Arteries are the tubes that carry blood away from the heart and veins are the tubes that return blood to the heart.

The blood from the lungs, which is full of oxygen, is often called red blood, as it looks bright red. Blood that has returned from the body back to the heart does not have much oxygen, and is often called blue blood because it has a darker blue colour.

Walls in the heart keep the red and blue blood separate, and valves (like one-way doors) keep the blood flowing in the right direction.

What causes a heart defect?

Sometimes there is a defect in the walls of the heart (e.g. a hole in the heart) or a problem with the valves (e.g. they may be too narrow or completely blocked). This means either the blue and red blood gets mixed up, or the heart may not pump very well. When these problems occur, the body may not get as much oxygen as normal.

Usually, a heart defect develops when the baby is still growing in the uterus. It is not caused by anything the mother did during her pregnancy, and often doctors cannot tell why the defect has happened. Sometimes heart problems are due to genetics (there is a family history of heart defects). Sometimes, certain illnesses in childhood cause damage to the heart.

Children can get problems with their heart after a viral infection (a virus). However, this is extremely rare.

When to see a doctor

If your child has any of the symptoms of a heart defect, see your GP. You will be referred to a paediatrician or paediatric cardiologist (children’s heart specialist).

There are several tests performed to diagnose heart defects, most of which are simple, quick and painless:

- Chest X-ray – a simple and quick X-ray of the chest.

- ECG (an electrocardiogram) – wires are attached with sticky dots on the skin of the chest, arms and legs. The wires record the electrical activity of the heart. It is very quick and your child won’t feel anything more than the sticky dots. Your child must lie quite still for about a minute, which can be tricky as small children tend to wriggle around.

- Ultrasound scan (an echocardiogram, or an echo) – a handheld scanner is placed on the chest and stomach and gives a picture of the heart on a TV monitor. Your child will feel some pressure as the scanner is pushed quite firmly. It is not painful but may be a bit uncomfortable.

Because your child must lie very still for these tests, sometimes they are given some sedation (medicine sedation to make them feel sleepy). This is usually a liquid they drink or a small squirt given up the nose by syringe. There are no needles involved.

Treatment for heart defects

The treatment for your child’s heart defect will depend on the cause of the problem. Most heart defects resolve by themselves over time, and some can be fixed with medicine. Sometimes surgery or other procedures may be needed. In some cases, your child may need a combination of treatments.

Medicine

For some heart problems, children can take medicine that can be stopped once the problem has improved. Sometimes medicines need to be taken for many years, or even for the child’s whole life.

Surgery

Heart surgery can provide a life-long cure for some heart conditions. A heart surgeon will discuss the risks and benefits with you in detail. Sometimes, surgery may be delayed until your child is older and stronger, which means they are able to tolerate the surgery better. Depending on your child’s condition, multiple operations may be needed.

In very rare cases where surgery, procedures or medicine does not help, a child may need a heart transplant.

Other procedures

Some procedures involve putting a thin tube, called a catheter, through the veins to the heart to treat the heart defect. Your child is given a general anaesthetic for this procedure.

How will a heart defect affect my child?

Some parents worry that their child might die suddenly. Fortunately, this is extremely rare for children. Most children with heart problems are successfully treated, and many live an active and healthy life.

It is understandable to feel very protective of your child if they have a heart problem. Yet many children can be independent, play competitive sports and do almost all of the things that other children do with very few restrictions. Check with your doctor about what level of physical activity is safe for your child.

If your child’s childcare centre, kindergarten or school is concerned about your child taking part in regular activities, or you are given conflicting advice by another health professional, talk to your child’s cardiologist and ask for a letter about what your child can or cannot do.